Tropical storm risk – Tropical depression in the Gulf: Tropical cyclone intensity change remains a forecasting challenge with important implications for such vulnerable areas as the U.S. coast along the Gulf of Mexico.

Analysis of 1979–2008 Gulf tropical cyclones during their final two days before U.S. landfall identifies patterns of behavior that are of interest to operational forecasters and researchers. Tropical storms and depressions strengthened on average by about 7 kt for every 12 h over the Gulf, except for little change during their final 12 h before landfall. Hurricanes underwent a different systematic evolution. In the net, category 1–2 hurricanes strengthened, while category 3–5 hurricanes weakened such that tropical cyclones approach the threshold of major hurricane status by U.S. landfall.

This behavior can be partially explained by consideration of the maximum potential intensity modified by the environmental vertical wind shear and hurricane-induced sea surface temperature reduction near the storm center associated with relatively low oceanic heat content levels. Linear least-squares regression equations based on initial intensity and time to landfall explain at least half the variance of the hurricane intensity change.

Applied retrospectively, these simple equations yield relatively small forecast errors and biases for hurricanes.

Characteristics of most of the significant outliers are explained and found to be identified a priori for hurricanes, suggesting that forecasters can adjust their forecast procedures accordingly.

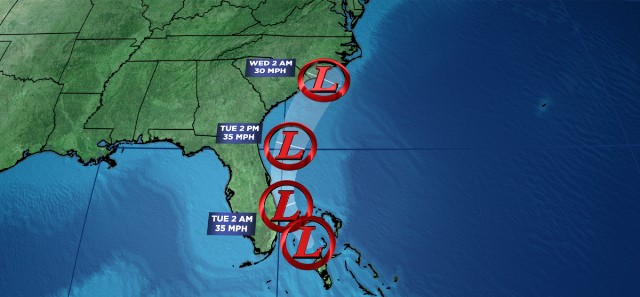

Tropical storm update in the gulf of mexico

Tropical cyclones1 can devastate the U.S. Gulf coast (e.g., Rappaport and Fernandez-Partagas 1995; Blake et al. 2007). The infamous Galveston hurricane of 1900 took at least 8000 lives and ranks as the deadliest single-day disaster in United States history. The loss of life (Beven et al. 2008) and the way of life suffered in 2005 from Hurricane Katrina show that the region remains at great risk.

About three tropical cyclones, including one hurricane, make landfall along the U.S. part of the Gulf Coast each year on average (e.g., McAdie et al. 2009). Over the past 30 yr, the Gulf coast accounted for almost two-thirds (34 of 54) of the hurricane landfalls in the contiguous United States.

A ‘‘major’’ hurricane (MH), category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale (SSHWS; Schott et al. 2010; Simpson 1974), strikes the northern Gulf coast almost every other year on average. While major hurricanes constitute only one-quarter of U.S. landfalling hurricanes, they cause around 85% of the damage (Pielke et al. 2008) and most of the fatalities (Blake et al. 2007).

Mitigating hurricane risk requires a more informed public, both well before and upon the final approach of a storm. Accurate operational tropical cyclone forecasts are essential. They are the responsibility of the U.S. National Hurricane Center (NHC) (e.g., Rappaport et al. 2009), a part of the National Weather Service (NWS). NHC’s track prediction errors have been cut roughly in half over the past 15 yr, mirroring gains in operational computer model guidance (e.g., Franklin 2009).

Tropical storm hurricane forecast

Significant improvements in storm intensity forecasts, on the other hand, remain an unmet goal spanning decades (e.g., Hebert 1978, p. 831). The inability to make consistently accurate intensity forecasts has led NHC to list intensity forecasting as its top priority for the research community (JHT 2009) and NOAA has made it a focus of their recently established Hurricane Forecast Improvement Project (HFIP 2009).

NHC’s intensity forecast errors in the Atlantic basin currently average about 10 kt2 for 24-h forecasts and 15 kt for 48-h forecasts (Franklin 2009), a range corresponding to roughly a one category interval on the SSHWS. ‘‘Rapid intensification,’’ or RI, when systems intensify by at least 30 kt (about two SSHWS categories) in 24 h, occurs about 6% of the time (Kaplan et al. 2010) and rarely, if ever, is forecast accurately by the NHC.

Kaplan et al. (2010) discuss three influences on tropical cyclone intensity change identified by Marks et al. (1998): inner-core, large-scale atmosphere, and ocean processes.

Their Statistical Hurricane Intensity Prediction System (SHIPS) developed for the Atlantic hurricane basin is among the best-performing intensity forecast guidance schemes available to operational forecasters (Franklin 2009).

Long range hurricane forecast

It is in this era of limited intensity forecast capability that a spate of tropical cyclones occurred recently over the Gulf of Mexico. From 2003–05, for example, 15 tropical cyclones–including eight hurricanes, made landfall on the U.S. Gulf Coast.

The behavior of these storms reinforced a perception held by NHC hurricane specialists (forecasters) and others (e.g., Vickery and Wadhera 2008) that strong hurricanes, like Katrina and Rita in 2005, often weaken in their final hours prior to landfall along the northern Gulf coast. Both of those hurricanes reached Category 5 intensity over the central Gulf before coming ashore at category 3 strength.

Tropical storm tropical depression

This study looks more closely at the intensity change characteristics of the Gulf of Mexico tropical cyclones before their U.S. landfall. It begins by examining a basic potential relationship between a storm’s ‘‘initial’’ intensity at periods of up to 2 days prior to landfall and its landfall intensity.

That focus is prompted by a combination of the forecasters’ perceptions, the reality that empirical intensity forecast methods remain competitive with more sophisticated approaches, and the observation that initial intensity information [sometimes expressed as a deficit from the maximum potential intensity (MPI), e.g., Emanuel (1988); Holland (1997)] contributes positively on average within the basin-wide framework to SHIPS. We seek to identify such relationships in the Gulf of Mexico region and the underlying causes for these systematic patterns of behavior.

The goal of this study is to provide hurricane forecasters with improved objective intensity forecast guidance that can assist them in this important and challenging science and service area.

Hurricane tropical storm forecast path

Tropical cyclones undergo systematic patterns of behavior when approaching the U.S. Gulf coast. Intensity change of tropical storms and tropical depressions is a strong function of time to landfall, but not of initial intensity.

On average, they strengthen by about 7 kt per 12 h, except for slight change during their final 12 h over water. Hurricane intensity change prior to landfall correlates strongly with initial intensity at all lead times (forecast periods) through at least 48 h. The variance explained by a linear fit to the initial intensity increases from 50% at 12 h before landfall to 92% at 48 h for hurricanes.

On average, category 1–2 hurricanes strengthen and category 3–5 hurricanes weaken by landfall, such that they approach the threshold intensity for major hurricanes.

This pattern of behavior can be partially explained by consideration of the maximum potential intensity modified by the environmental vertical wind shear and hurricane-induced sea surface temperature

reduction near the storm center as storms approach the northern Gulf coast. The high OHC regions in the central Gulf are very deep mixed layers, which prevent the SST reduction. The OHC in the northern Gulf is much lower, however; so, the SST reduction lowers the average shear-modified MPI to the category 2–3 threshold.

Simple predictive linear regression equations applied to the dependent database for hurricanes yield relatively small forecast (‘‘hindcast’’) errors compared to the model guidance and official forecasts. They could provide useful guidance during future hurricanes, and even more so when systems can be identified and excluded at forecast time as belonging to one of the following outlier groups:

- hurricanes with a Gulf roughening period PrG (extent of 34-kt winds in the direction of motion divided by the forward speed) # ; 6 h;

- hurricanes with a PrG of more than about 20 h, for example, by stalling, moving slowly (,;5 kt), or looping; and

- hurricanes with an inner-core convective structure significantly disrupted by a previous passage over land.

Tropical storm risk

In the first exception, a hurricane stronger than predicted by the equations, with possible RI, should be anticipated. For the latter two cases, the system can be expected to be weaker than projected by the equations.

For real-time and training considerations, applying operationally the concepts and equations presented here could require some forecaster and end-user recalibration, especially for MHs.

The findings in this study suggest a follow-on line of work. The importance of Gulf tropical cyclones and their intriguing behaviors imply that a regional version of the SHIPS program (perhaps limited to hurricanes) could be useful for forecasters. For example, the impacts of OHC in this study appear to be more important than in the basin-wide version of SHIPS, which could be due to the larger gradients of OHC in the Gulf compared to the Atlantic basin as a whole.

A Gulf-region version of SHIPS, potentially using a higher-resolution OHC climatology (e.g., Shay and Brewster 2010), could provide a step toward meeting the HFIP goal of a 50% improvement in intensity forecast guidance, at least for this important subset of tropical cyclones that accounts for most U.S. hurricane landfalls.

Hurricane names

- List of 2019 Atlantic Hurricane Names:

- Andrea.

- Barry.

- Chantal.

- Dorian.

- Erin.

- Fernand.

- Gabrielle.

- Humberto.

Tropical Storm Risk

Once a hurricane has formed, it can be tracked. Scientists can usually predict its path for 3-5 days in advance. They can only say that there is a five percent chance of a major hurricane hitting the coast from April to November.

The 2019 Atlantic hurricane season starts on June 1 and will run until Nov. 30. However, Subtropical Storm Andrea has already formed, making 2019 the fifth consecutive year to have a named storm outside of the Atlantic hurricane season.

Tropical systems usually form in the Gulf of Mexico or off the east coast of the United States. Since 1851, a total of 81 tropical storms and hurricanes formed in the month of June.

On average, 10 named storms occur each season, with an average of 6 becoming hurricanes and 2 becoming major hurricanes (Category 3 or greater).

Researchers at Colorado State University are maintaining their prediction of a near-average 2019 hurricane season. Updated projections released on Tuesday predict 13 additional named storms will form in 2019, with six becoming hurricanes and two classified as major hurricanes.

The most read

Types of Cargo Ship

CRANES FOR CONTAINERS: mobiles, installed in a fixed way on a foundation column cranes on rails, gantry, telescopic. Container handling equipment

Ship to Shore Crane

The gantry crane for containers: panamax, post panamax, operator, uses, characteristics, ports, docks, transport, maneuvers, parts, container